1.4.1 Sexuality

A repressed sexuality

In the biography of Christina Rossetti is said that when she was only seventeen, she and James Collinson, one of the first members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, met and fell in love with each other. He had been one of those who, following the example of Newman in those troubled years of the later ‘forties, had joined the Roman Communion, which, however, he left again for the sake of Christina, who had first of all refused him from a sense of loyalty to her own branch of the Church. The courtship went on for some time, and Christina and her brother William paid visits to the Collinson family. But the prospect of his earning sufficient to marry on seemed remote, and, when in 1850 he again decided to become a Roman Catholic, Christina broke off the unofficial engagement. Having formally resigned his membership of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Collinson sold his easel and lay-figure and entered a Jesuit College with the idea of becoming a priest. The Seminary authorities, feeling it necessary to test the sincerity of this somewhat fickle-minded young man, set him first of all to the task of cleaning shoes–‘ as an exercise in humility.’ This, however, was not what Collinson expected, and accordingly he gave up the idea of entering the priesthood and resumed his former occupation as a very indifferent painter.

It was ten years after this, when Christina was thirty, that another and far stronger love came into her life. This second lover was Charles Cayley, the scholarly translator of Dante. Their temperaments were well suited to each other; their tastes and sympathies were akin–in every respect save one. But Cayley could not share the Faith which to Christina was more than life itself, and for that reason she refused to marry him. ‘Although she would not be his wife,’ says her brother William, ‘no woman ever loved a man more deeply or more constantly.’ Their friendship remained a life-long one, and when Cayley died some twenty-five years later, he left all his manuscripts and other treasured possessions to Christina.

So, as you can see she left both men by her religion because in any place she says that she didn’t like them. Obviously, her sexuality was trunked by religion and she needed to let off steam with something. We realize she used verses to expel her hidden sexuality and Goblin Market is an example.

On the other hand, Jan Marsh proposed in her biography Christina Rossetti: A Writer’s Life (1995) that Christina was sexually abused by her father, but “perhaps like many abuse victims she banished the knowledge from conscious memory.” However, this kind of speculative claims become highly popular in biographies in the 1990s. We don’t know if it was true but one thing is clear: Christina Rosseti didn’t carry her sexuality out like she would have liked. A sign of this is the poem that I have chosen: Goblin Market. Through it she expresses her most deep sexual yearnings talking about fruits and using other terms.

Moreover, Christina as a teenager seems to have been quite attractive if not beautiful, so if it hadn’t been by her education she had had a lot of suitors.

Her repressed sexuality would be a burning point from the double personality of Christina Rosseti’s: on the one hand we have a shy and oppressed Christina Rossetti and on the other hand, a seductive and a eager woman of changing her society and believes.

Now, we are going to see all of which is related to sexuality in the poem ‘Goblin Market’:

Despite that notion that most of Christina Rossetti’s poetry was an inspiration of her stark Christian faith, there is a dark sexuality inside the “Goblin Market.” What more controversial Christian notion is there than that of sexual temptation being the downfall of mankind. In “Goblin Market” Rossetti shows how the strength and fortitude of one woman against the temptations of sexual evil is enough to free someone she loves from the punishment of damnation.

From the very first stanza, with its descriptions of luscious fruits for sale in the “Goblin Market,” some hard to find but summer ripe, one cannot help but read these mouth-watering depictions with sexuality in mind. Rossetti’s reference to things like “[p]lump, unpecked cherries” (7), “[p]omegranates full and fine”(21) and “[f]igs to fill your mouth” are subtle in their reference, but “sweet to tongue and sound to eye” lead the reader along in a dizzying petition to feed a sexual appetite.

Enter Laura and Lizzie to confirm this sexual petition when Laura declares:

“We must not look at goblin men,

We must not buy their fruits:

Who knows upon what soil they fed

Their hungry, thirsty roots.” (42-44)

It isn’t safe, Laura says, to just lie with any old man and give him all of you. You never know where he’s been. The goblins continue to parade their wares, showing off their rich, delicate dishes and fruits. Lizzie drowns out the sound of their calls, but Laura is intrigued by their strange and different appearance, and as they chant and sing she hears them sound “kind and full of loves” (79). At that moment, Laura is lost to their temptation. How bad can it be? As the men tramp back up the hill toward her, Laura eyes them curiously. They weave her a crown of “tendrils, leaves and rough nuts brown” (100), (symbolic of the pagan Harvest Queen’s sexual sacrifice for the land).

Temptation soon takes hold of Laura, and though she has no coin to offer, the Goblins note that her hair is gold enough, and with a single tear as her regret, she clips a curl and begins to feast. It is that moment between maiden and woman that signals her tear, but she longs so desperately for womanhood that she feasts and feasts until her body can take no more. In a very stark portrayal, Rossetti’s sexual depictions cannot be denied: Laura “sucked their fruit globes fair or red” (128) and the juices are described as “stronger than man-rejoicing wine” (130). Laura “sucked until her lips were sore” (136), then in a daze wanders home alone.

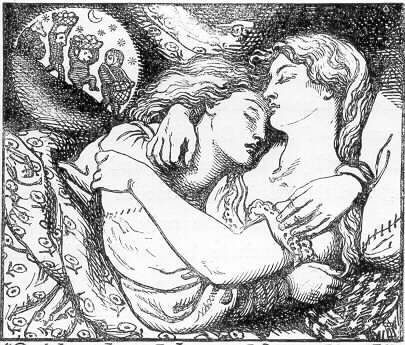

As Lizzie meets her at the gate it takes a moment before she realizes what has happened. Lizzie begins to lecture Laura about their friend Jeanie, who she’d pined away until she died to taste that fruit again. Laura doesn’t seem concerned, and promises she’ll go back tomorrow and bring Lizzie back all of the delicious fruits that she can carry. In the next stanza Rossetti describes the two girls going to bed together, two flowers on the same stem, “two wands of ivory / tipped with gold for awful kings” (190-191) and as they sleep they do so “cheek to cheek and breast to breast”, a very innocent description of two young girls who know not the horrors and hardships of womanhood.

The change in Laura is evident the next day. As they work, Laura is far away in a dream and longing for the night to come so she can experience the bliss she knew the night before. As the day crawls to a close, Lizzie is ready to head home, but Laura lingers in wait for the Goblin Men to return. They do not, until Lizzie alone declares that she hears their cry, but Laura can no longer hear them. Upon realizing that the follies and freedom of yesterday have forsaken her, Laura falls into a deep depression, and longs only to end her suffering with death.

Not able to stand the thought of losing her beloved sister, Lizzie finally takes a silver coin and sneaks off to the Goblin Market. Lizzie offers them her coin, and the Goblins beckon her to eat with them, but Lizzie refuses. She wants to take the fruit home and give it to her waning sister, but the Goblins do not give her what she wants, and their previously happy demeanor begins to change.

The taunts they begin to throw at her suggest that she has turned down their petitions for intimacy, “One called her proud, / Cross-grained, uncivil”(394-395). They begin to hassle her, and it becomes physical, a very realistic portrayal much like rape where they claw and tear her gown, soil her stockings and rip at her hair. She keeps her mouth (body) closed as they squeeze their fruits against her lips and try to force her to eat. Like a feminine Christ-figure, she stands alone against adversity, and Rossetti describes her:

“Like a royal virgin town

Topped with gilded dome and spire.

Close beleaguered by a fleet

Mad to tug her standard down” (418-421).

But no matter how they bullied and beat and bruised her, Lizzie “Would not open lip from lip” (431). At last they give up and begin to disappear, leaving her alone and aching on the ground. She walks home and rushes into her sister crying, “Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices, / Squeezed from goblin fruits for you, / Goblin pulp and goblin dew” (468-470). The sexuality continues as she tells her, “Eat me, drink me, love me; / Laura, make much of me” (471-472), suggesting that the sin of sexual indulgence with unknown men has left her longing, but Lizzie can return her to youthful innocence again. And though Lizzie has not tasted the fruit, her sacrifice is enough to free Laura of the spell she’s under, and liberated she falls into a sleep that could be life or death.

As the story winds down, Laura is revived and young again, with no sign of death or doom, and no single thread of silver in her golden hair. When both women are wives later down the road and with children of their own, Laura tells the story of what Lizzie did for her. The final note leaves one in wonder if Rossetti is not warning her feminine readers to forsake the love of men, and give the tenderness of their hearts to their sisters instead. A sister will not harm you, beat you or charm you, but sacrifice her own soul to keep her sister’s pure, “[f]or there is no friend like a sister; / In calm or stormy weather” (562-563).

The forlorn and forsaken female, damned by her love for a man, appears elsewhere in Rossetti’s poetry, suggesting that perhaps Rossetti, who never married, felt jilted in love. It is likely she found more comfort in her religion and the company of her closest friend and sister, Maria Rossetti, whom she dedicated “Goblin Market” to.

From another point of view, the unmistakably sexual character of the scene of Lizzie’s return from the goblin market can lead us to assume that the “sisters” are either not sisters at all, or are engaged in an incestuous relationship. Nowhere in the poem does the incest taboo make itself felt, explicitly or implicitly, and although an analysis of this silence and omission is possible, it is sufficient to acknowledge the existence, or emergence of a lesbian relationship between Laura and Lizzie. This opens the way for a reading of “Goblin Market” as a story of Laura’s coming to terms with her (homo)sexual orientation.

The act through which Laura “falls” – buying the fruit from the goblin men with a lock of her hair, which metonymically stands for her body – is her initiation into sexuality through heterosexual prostitution (in fact, in “Goblin Market”, heterosexuality equals prostitution). Her desire finds a socially acceptable outlet in the goblin men and their phallic fruits, but simultaneously, the fruit is immediately denied to her; she no longer sees the goblins or hears their cries. This tension illustrates the conflict between the obligatory heterosexuality that society forces on Laura – and the demand that her sexuality be cast in terms of trade and (male) ownership – and her actual desire, which Laura half-realizes but cannot articulate. Indeed, she has no language in which to describe herself and her sexuality, save that which she borrows from the goblins. Therefore, her dissatisfaction with the goblin men and her longing for another kind of experience, a longing so completely unacceptable and conflicting with the societal standards which she has internalized, cannot manifest itself in words, or indeed in her consciousness; it takes instead the form of “removing” the goblins from her perception completely. This internal conflict literally burns Laura up from the inside – she weeps, suffers and falls ill. It is only when Lizzie provides her both with the words to articulate her needs and the actual sexual contact that she so desires that Laura is at last able to perceive that the goblin fruits taste bitter; embracing her “sister”, she also embraces a lesbian identity and is able to be at peace with herself. The ending of the poem, which mentions that the “sisters” are married and have children, does not contradict such an interpretation. Although they are referred to as “wives”, their husbands are never mentioned at all, and neither is the nature of their relationships with Laura and Lizzie – suggesting, perhaps, a sort of “white marriage” for the sake of Victorian propriety. In the light of this reading, Lizzie’s perception of the goblins as dangerous and her ability to resist their attempt at rape can be attributed, at least in part, to the strength stemming

from her awareness and acceptance of her sexuality; the silver coin she takes with her signifies economic independence, but also the moon and thus femininity. The image of the sisters sleeping together, which puzzlingly follows Laura’s return from the goblins – no doubt a betrayal of their “sisterly” relationship – testifies to the strength of their bond, which allows them to oppose the oppressive norms of society and define themselves as individuals. At the same time, the very word “sister” indicates the necessity to conform, at least in some measure, to those norms, which designate lesbian sexuality as nonexistent, impossible or threatening

(or nonexistent because it is threatening to the patriarchal Victorian social order).

The most noticeable aspect of “Goblin Market” that seems immediately to distinguish it from other works of the time period is its verbal opulence and sensuous imagery used in the description of the fruit for sale by the goblin men, which seems to further illustrate its significance:

…Plump unpecked cherries,

Melons and raspberries,

Bloom-down-cheeked peaches,

Swart-headed mulberries,

Wild freeborn cranberries,

Crab-apples, dewberries,

Apricots, strawberries; —

All ripe together

In summer weather, —

Morns that pass by,

Fair eves that fly;

Come buy, come buy:

Our grapes fresh from the vine,

Pomegranates full and fine,

Dates and sharp bullaces,

Rare pears and greengages,

Damsons and bilberries,

Taste them and try…

The emphasis, then, is on the fruit and its importance, and also on the goblin men, which seems further to stress the danger of temptation, and also references the Biblical fall from grace due to an inability to resist the fruit. Critics have made references to the fruit in “Goblin Market” being linked to sex.

We can see a link to the fruit as a sex symbol because the “joys brides hope to have” are implicitly identified with Laura’s powerfully sensual experience with the goblin fruit, defining her temptation by the goblin men as a sexual one. Furthermore, “the premature and illicit experience of such “joys” causes Jeanie to become a “fallen” woman. The descriptions and subsequent implications of the fruit perhaps run counter to the expectations of Rossetti’s staunchly conservative Victorian society, and coming from a very religious Victorian woman, it seems unlikely that the poem would contain so many dramatic descriptions. I believe that this could be an example of the repressed feelings that so many members of Rossetti’s society probably felt, this poem can be read as a monitory exemplum and thus an extreme instance of Victorian sexual repression. “It reflects a profound fear of female sexuality and its potential consequences. Rossetti’s unrelenting attacks upon the indulgence of sexual desire, often troped as an illness or represented as an addiction that produces malaise, disease, or death for narrators and characters in her poetry, was absolutely intentional, and this makes sense when we consider how religious Rossetti was.

Although Rossetti seems to be rather uncaring for those two particular men with who she had a relationship, she did seem to want to be married and placed in the role of wife and mother, something which she seems to valorize at the end of “Goblin Market”.

To sum up, homosexual or heterosexual but it’s no doubt Christina Rosseti shows through the poem references to sexuality, in her case self-controlled with a view to Victorian society. Her real personality appealed to a sexual life much more active than the way of living which Christina had adopted.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)