2.3.2 Sister

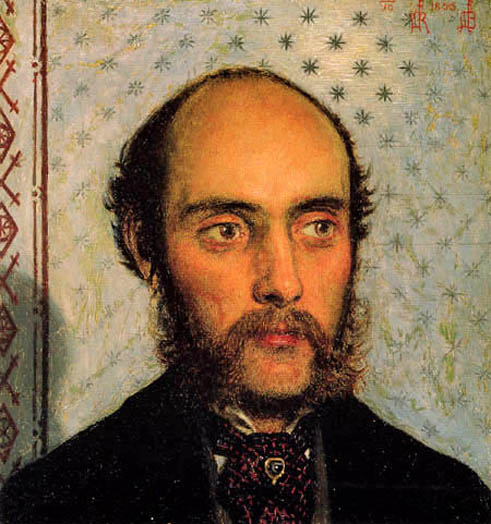

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

(masculine action)

Vs.

Christina

Rossetti

(feminine

submission and

patience)

an 1886 essay William Sharp, the devoted friend of Dante Rossetti and an intimate of the whole Rossetti family, made a statement that most present-day students of the Pre-Raphaelites would find startling. Four years after Dante Rossetti’s death he compared the popularity of Christina Rossetti’s poetry with that of her ostensibly more famous brother:

“The youngest of the Rossetti family has, as a poet, a much wider reputation and a much larger circle of readers than even her brother Gabriel, for in England, and much more markedly in America, the name of Christina Rossetti is known intimately where perhaps that of the author of the House of Life is but a name and nothing more.”

Although we might be skeptical that various prejudices molded Sharp’s opinion, evidence suggests that it was widely shared. Two years later a writer in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine insisted that “Christina Rossetti’s deeply spiritual poems are known even more widely than those of her more famous brother”. Clearly at work in these evaluations is an implied distinction between popularity and notoriety. For most readers Christina Rossetti’s poems were more accessible than those of her brother, but her work was also and distinctively more compatible with the fundamental aesthetic (as well as moral) values of its audience. As Sharp further noted, “she has all the delicacy and strength of her brother’s touch, but she is free from the frequent obscurity or convolution of style characteristic of Dante Gabriel Rossetti in his weakest moments”.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work featured women in the conventional Victorian perception of either the virginal unspoiled Madonna or the fallen woman or temptress in need of rescue by man. Never is she a player in her own right but merely the object of the viewer’s gaze alone. His sister, the poet Christina Rossetti, an admirer of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, was equally captivated by medievalism and fantasy, and frequently used women in her work as did her brother, however the similarity ends there. Christina’s poetry depicted women as the victims of men and the avengers of those victims. Her fallen women are not saved by men but by their own resolve or by the assistance of other women. This remains the fundamental question that separates the two siblings work.

Christina Rossetti, often was overshadowed by her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti, struggled to express her own independent authorial voice. This is the question and one of the most highlighted reasons which explain why she wasn’t included in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Sometimes it is thought her brother William also contributed to her exclusion.I think so because he was a man and he was in favour of her first-born brother, Dante Gabril Rossetti. On the contrary, it is said William was who encouraged Christina Rossetti to submit her poems for publication because he thought her sister was ‘the best if the batch’ in writting sonnets. Moreover, the first collected edition of her works, with biography, was published in 1904 under the editorship of her brother William and he expressed about her sister: ‘Her life had two motive powers-religion and affection- hardly a third’. It is true religion and affection marked her life but not with the same sense her brother William and others thought. Christina used religion as a way of changing society and she expressed an inner repressed sexuality in her works such as Goblin Market closely related with her personality.

It is obvious William Michael Rossetti hadn’t any idea about her sister’s yearnings but it didn’t mind in the Victorian Era; a society in which women were out of place. Women were branded with the following adjectives: puritan, shy, virgin, innocent,conformist, naive, etc. So, in Rossetti’s house the first-born Dante Gabriel Rossetti was the choral voice, William was his follower and the two sisters were put aside: Christina’s sister (Maria Francisca) became a nun and she became famous after her death.

William wasn’t the choral voice in Rossetti’s family but he criticized his sister, too. He commented that his sister’s “habits of composition were entirely of the casual and spontaneous kind, from her earliest to her latest years” and it has stimulated much critical discussion. Thomas Swann comments: “Christina was not the craftsman her brother was. She wrote simply, often carelessly, and she did not like to revise.” He also says: “The best whimsy is spontaneous and not the product of conscious artistry” (he feels Christina’s whimsy is superior to that of her brother, Dante Gabriel, and the other Pre-Raphaelites). To contend that Christina Rossetti did not revise, was not a conscious artist, is quite simply wrong. As Packer and others have shown, she was a careful artist who conscientiously revised her work. Virginia Woolf’s centennial essay, “‘I Am Christina Rossetti’,” is perhaps the best description of Rossetti as an artist. Addressing the poet herself, Woolf writes:

‘I doubt indeed that you developed very much.

You were an instinctive poet. You saw the world

from the same angle always. [. . .] Yet for all its

symmetry, yours was a complex song. When

you struck your harp many strings sounded together.

Like all instinctives you had a keen sense

of the visual beauty of the world. [. . .] A firm

hand pruned your lines; a sharp ear tested their music.

Nothing soft, otiose, irrelevant cumbered your pages.

In a word, you were an artist.’

Although her best work, including Goblin Market, may have arisen spontaneously from the unconscious, even as she wrote Rossetti applied consciously her craft as a poet. It could be no other way. Many critics have remarked on the eccentric meter and rhythm of Goblin Market, and many note how Rossetti adapts that rhythm to meet the requirements of the mood and/or imagery she is conveying. This is the work of a true artist.

On the other hand, I am shocked when I see Christina Rossettis features as a virgin because it wasn’t her yearning or her aspiration in the life at all. But when she was young her brother Gabriel would sometimes use her as a model for his paintings; perhaps the best-known is his ‘Ecce Ancilla Domini’ in which she features as a Virgin.

As we have seen previously , Christina Rossetti’s poetry would have entered in Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood perfectly but the problem comes when one tries to apply the qualities of her poetry to the business of interpreting her life. It seems safest to the Victorian society seeing the romantic-fantastic-depressive side to her work as being in harmony with the imagination of her brother and his associates. She was an admirer, for instance, of Swinburne (although she had to stick strips of paper over his anti-religious lines in order to enjoy his poems) and nobody accuses Swinburne of revealing himself in his poetry, in which similar romantic fancies appear. So, if her brother hadn’t existed, although being a woman, she would have reached much more consideration and fame. Without any doubt, her brother wasn’t interested at all in his sister because he knew if her poems were published, it would originate a great commotion and stir in literary society and he would keep aside. Dante Gabriel rossetti took the opportunity from the weakness around power women had in his era to exclude her sister from the Pre-Raphaelitism Movement, from which he was the founder and the major precursor of the Aesthetic movement. Without question and much to my regret, Dante Gabriel Rossetti held the winning cards and he diminished the spread of her success. In a famous remark, Gabriel once said to Christina, “You may be a singing-bird; but you dress like a pew-opener.” This remarks the difference between being a free woman and living enslaved in male morals. The expression ‘singing-bird’ comes from Christina’s poem:

A BIRTHDAY

My heart is like a singing bird

Whose heart is in a watered shoot:

My heart is like an apple-tree

Whose boughs are bent with thickset fruit;

My heart is like a rainbow shell

That Paddles in a halcyon sea;

My heart is gladder than all these

Because my love is come to me.

Raise me dais of silk and down;

Hang it with vair and purple dyes;

Carve it in doves and pomegranates,

And peacocks with a hundred eyes;

Work it in gold and silver grapes,

In leaves and silver fleurs-de-lys;

Because the birthday of my life

Is come, my love is come to me.

I consider this poem one of the most optimistic Christina’s poems. Here, she feels happy (even she sings). Her heart like ‘an apple-tree’ is a great comparison to explain that her heart is big, full of life because she is in love and she hopes that this love is going to come. Being a ‘singing bird’ is her major wish, being far away from male control.

Both brothers were selfish because while at the end of 1850s William settled as an excise officer and art critic and on the other hand, Gabriel as a remarkable painter (click the video below) and poet; Christina who was called ‘the sister’ was immersed in a severe depression.

Finally, maybe some people could say: ‘in 1862 were published her works, so her brother was kind with this’ but I would answer: ‘ Did somebody know about Ellen Alleyne?’. Her ‘dear brother’ didn’t make any favour because he published her works but his trick was to invent a pseudonym for her. So Christina Rossetti wrote for The Germ under the pseudonym ‘Ellen Alleyne” invented by her brother Dante Gabriel. Her Goblin Market and Other Poems brought a popular attention and a critical acclaim, as did her devotional poems and essays but anybody associated it with Christina Rossetti’s face.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)